Meanwhile in Russia

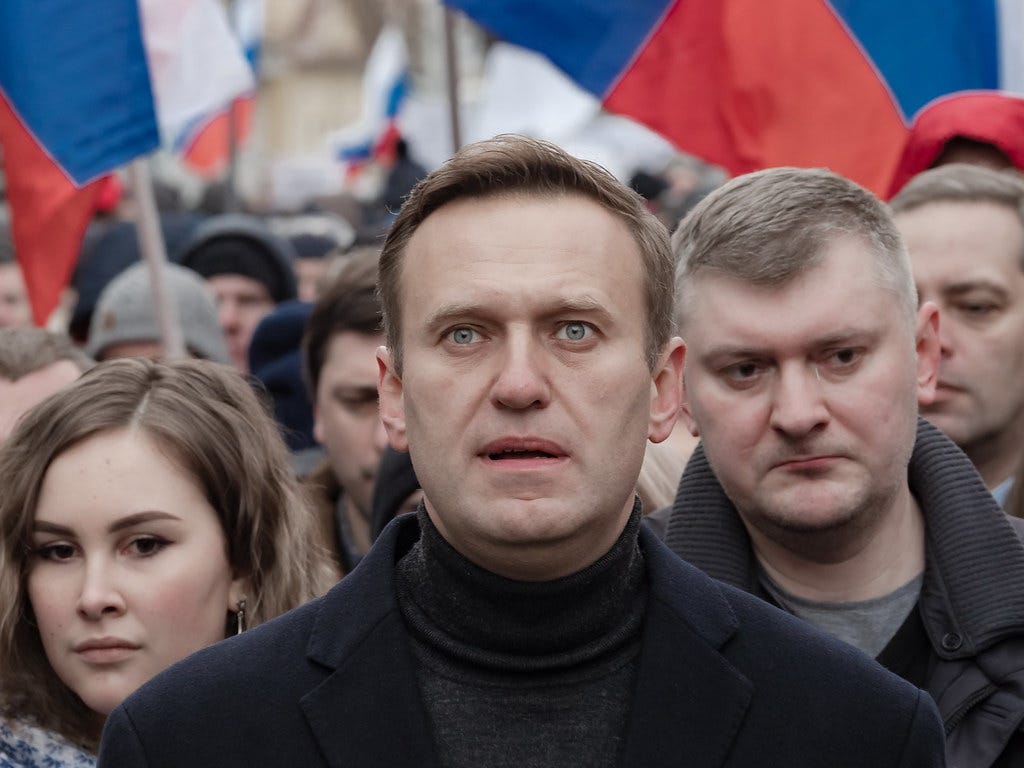

Politics, poison, and protests: Alexei Navalny leads unprecedented demonstrations in Russia from his jail cell

In a rush? No worries! The most important bits are in bold. Skim ahead!

Thousands were arrested on Saturday after unprecedented protests erupted across Russia over the government’s treatment of de-facto opposition politician Alexei Navalny. Navalny, currently in pretrial custody until February 15, spent the past five months receiving treatment in Germany after he was poisoned with a nerve agent by members of the FSB (Russia’s main security agency and the successor of the Soviet-era KGB).

The anti-corruption blogger turned opposition politician is Putin's fiercest critic, and someone the Kremlin is keen to eliminate. But in an act of defiance, Navalny returned to Russia on January 17. “I know I’m right. All legal actions against me are fake,” he said in a statement upon arrival in Moscow. Minutes later, he was arrested under the pretense of violating terms of a suspended prison sentence, terms he could not attend to because he was in recovery.

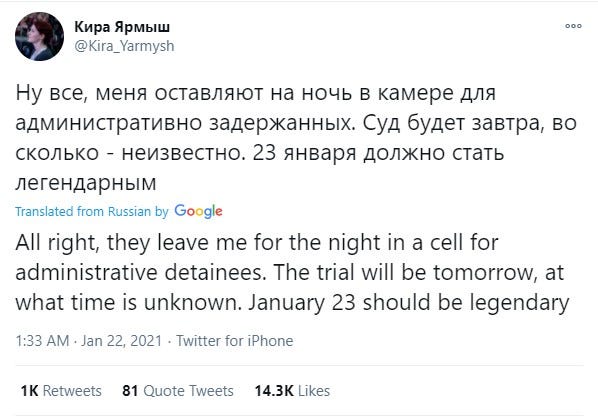

A savvy social media user, Navalny has used YouTube and Twitter to rally people and garner support for years. Last Monday, Navalny released a video, urging people to protest. “They are afraid of those people who can stop staying silent and realize their own strength,” he said. “I call on you to stop being silent, resist and take to the street.” On Tuesday, Navalny’s team released a video of their investigation into Putin’s Black Sea palace which was allegedly purchased using illicit funds provided by oil chiefs and billionaires. By Friday, the video had over 50 million views on YouTube. The Kremlin strongly denied the claims and arrested Navalny’s press secretary. She continued to tweet from jail, calling on people to attend protests.

Navalny also released remarks from jail on Friday, assuring supporters that he felt optimistic and was not planning on harming himself, in case anything mysteriously happened to him. Meanwhile, videos about Navalny, Putin’s palace, and Saturday’s protests flooded TikTok. By Thursday, “practically seven out of every 10 videos were on that topic [Navalny],” said popular TikTok user Slava Varfolomeyev to BBC Russian. One viral video by @neurolera, an English-language teacher, teaches protesters how to pretend to be American tourists if police question them. “I’m American,” she says in an exaggerated American accent. “You are violating my human rights!” And if that does not work, she advises people to say, “I’m gonna call my lawyer.” Russian authorities removed several posts, but the match was already lit.

When Navalny returned to Moscow, determined to create systemic change, some questioned whether Russia was ready for a revolution. On an Instagram live conversation, CNN correspondent Clarissa Ward said that based on the data available, although Russian people are “beginning to sour on President Putin… it does not appear that the majority of people in any way support a real shake-up of the system.” To some, however, Saturday’s sweeping protests show some shift.

“There was this heavy feeling that Russian public opinion had hardened in cement, as though it was stuck in a dead, hidebound ball,” said Vyacheslav Ivanets, a lawyer in the Siberian city of Irkutsk who took part in the protests. “Now I feel that the situation has changed,” he told The New York Times.

Tens of thousands of people participated in the largest anti-government protests Russia has seen in years. Despite warnings from law enforcement, people filled the streets to voice their anger over Navalny’s imprisonment and frustrations over the corruption ravaging Putin’s Kremlin. In Moscow, people chanted “Freedom to Navalny” and “Putin go away!” While Moscow and St. Petersberg saw the largest turnout, at least 109 cities participated. The New York Times reported, “on the island of Sakhalin, just north of Japan, hundreds gathered in front of the regional government building and chanted, ‘Putin is a thief!’” In the sub-Arctic city of Yakutsk, a smaller demonstration was held, despite temperatures dropping to -63 degrees Fahrenheit (-53 Celsius).

“I’m tired of being afraid. I haven’t just turned up for myself and Navalny, but for my son because there is no future in this country,” said Sergei Radchenko, a protester in Moscow, to Reuters.

Videos showed protesters in Moscow pelting snowballs and kicking government vehicles, even though throwing objects at the police is a crime in Russia. Some marched to the prison where Navalny is being held. Authorities met the protesters with restrained violence, using batons to disperse crowds, but resisted using harsher methods like tear gas. The Kremlin promptly condemned the protests via Russian state media, noting the “wave of aggression” could result in jail time for participants. Nevertheless, more protests are for planned next weekend, to try to free Navalny from what one ally, Leonid Volkov, called, “the clutches of his killers.”

The U.S. state department condemned the “use of harsh tactics against protesters and journalists,” and called on Russian authorities to “release all those detained for exercising their universal human rights and for the immediate and unconditional release of Alexei Navalny.” The U.K. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab also denounced the “use of violence” and urged authorities to release the arrested. On Monday, the EU foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell plans to discuss the issue with the bloc’s foreign ministers. But many Navalny supporters believe more action must be taken. Putin has survived previous protests and polling data, although questionable in tightly controlled Russia, shows little indication that people want drastic leadership changes.

Before Saturday’s protests, Ward explained that tweets, sentiments, and speeches, “unless it’s part of the architecture of a broader, coherent strategy for dealing with a specific state actor, then it’s essentially just virtue signaling.” She believes what, “people who support the opposition in Russia would like to see more broadly from the West is a coherent, coordinated strategy for dealing with Russia.” Although Europe imposed some sanctions, Ward said that unless the U.S. takes a “forceful role” in dealing with Russia, then “you’re not going to see any changes to Russia’s behavior.”

Go deeper: Watch the entire Instagram live conversation between Clarissa Ward and Hala Gorani here:

Deutsche Welle correspondent Emily Sherwin reiterated that “if there are sanctions, if there are words condemning Russia from the EU as we’ve been seeing, that kind of in the sense is old news for the Kremlin and they’ll probably just continue doing what they want.”

Navalny rose to fame in 2008 over blog posts revealing malpractice in Russian politics and major state-owned companies. He returned to Russia from Germany to ensure he did not become irrelevant to the Russian people by living in exile. Navalny plans to compete against Putin in September's parliamentary elections.

On August 20, on board a flight to Moscow from Tomsk, Navalny approached a flight attendant and said, “I was poisoned, I’m going to die,” before collapsing in pain. The flight made an emergency landing and he was rushed to a hospital’s intensive care unit where he fell into a coma. Two days later Navalny was airlifted to Berlin, where doctors confirmed he was poisoned and toxicology tests showed “unequivocal evidence” of Novichok.

Go Deeper: Everything you need to know about Novichok

For Navalny, the culprit behind the attack was undoubtedly Putin himself. “I understand how the system works in Russia,” he told CNN. I understand that Putin hates me, and I understand that these people who are sitting in the Kremlin, they arranged to kill me.” The Novichok attack was an operation more than three years in the making, showed a CNN-Bellingcat investigation.

In a deeply embarrassing episode for Putin, Navalny prank-called a member of the FSB’s toxins team pretending to be an official from the National Security Council. In the phone call, the FSB agent revealed Novichok had been placed in Navalny’s underpants. The Kremlin called the phone call “fake,” and denied the attempted assassination. In a press conference Putin, who refuses to say Navalny’s name, deemed he was too insignificant to kill, noting, “if [they] wanted to [kill Navalny], they would’ve probably finished it.”